The right to public space is a fundamental right for citizens to use for gatherings and various activities. When cities plan and build, planners must consider the existence of these spaces, including gardens, squares, sidewalks, beaches, and recreational areas, in addition to commercial centers, residential areas, and roads.

In Egypt, the state has become more sensitive to public space since the January 25, 2011 revolution. However, there is a clear trend towards the systematic reduction of public space. In Alexandria, a coastal city known as a summer resort and public breathing space for Egyptians, there is a problem with the management of public space, whether it be beaches, gardens, public squares, or even sidewalks that can be blocked to pedestrians.

Due to the "fluidity" that characterizes the Egyptian people, they are not bound by boundaries and do not conform to systems. We always find ways to circumvent the system, even if it is good and justified.

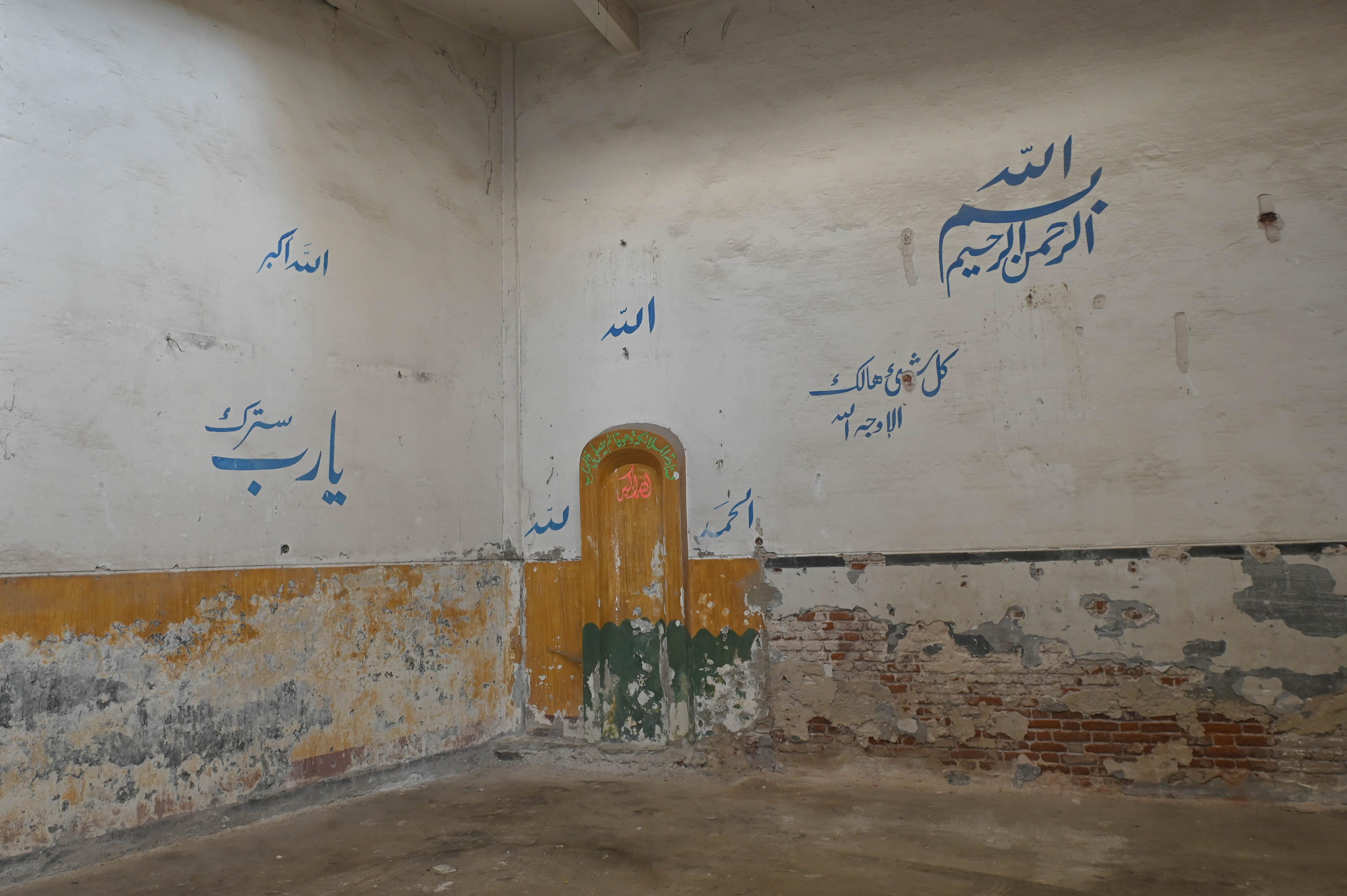

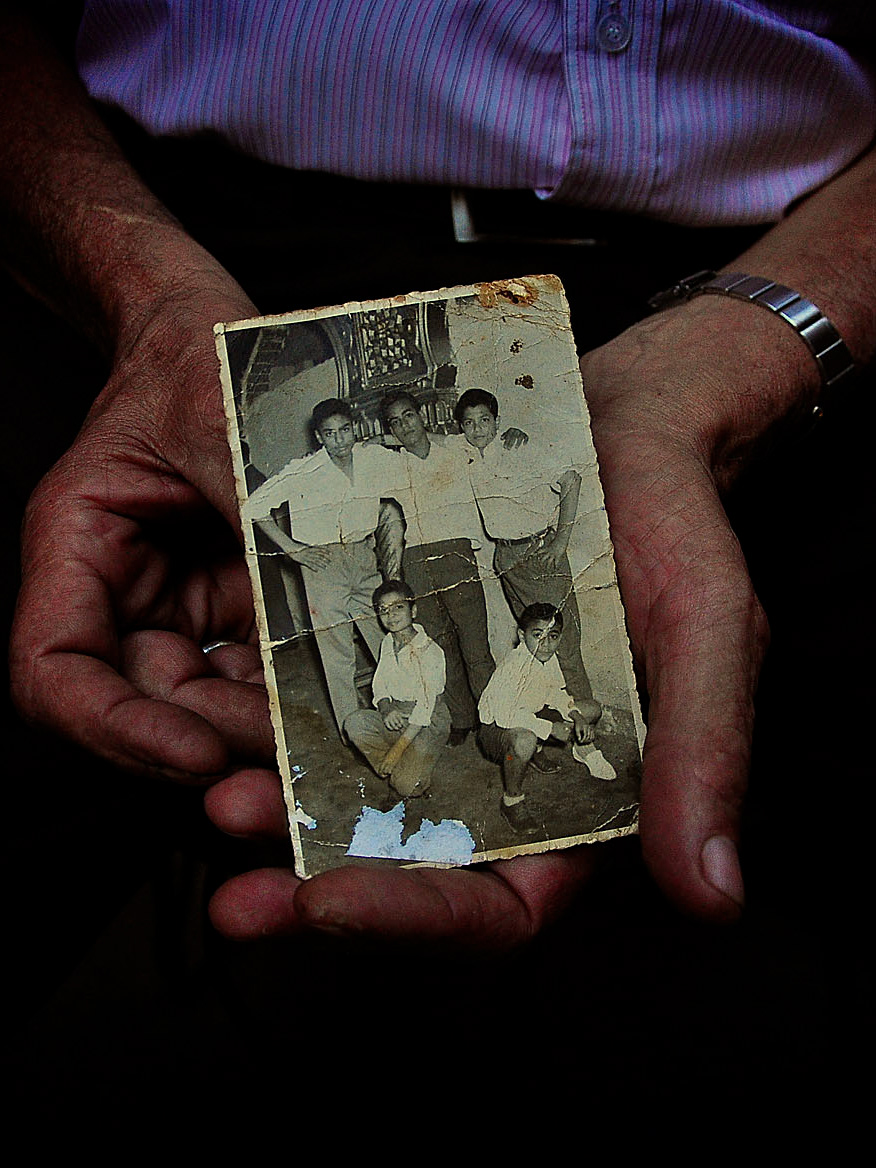

Wherever you go in the streets of Alexandria, you will notice the phenomenon of random prayer mats in the streets, on sidewalks, or in building entrances. You may wonder, as I did, about the existence of nearby mosques and prayer corners that would make it unnecessary for men to pray in these places and provide them with bathrooms, water for ablution, or a suitable place to pray. You may also be surprised to find mosques, large or small, next to these prayer mats. So the question remains, why are these mats and these worshipers there?

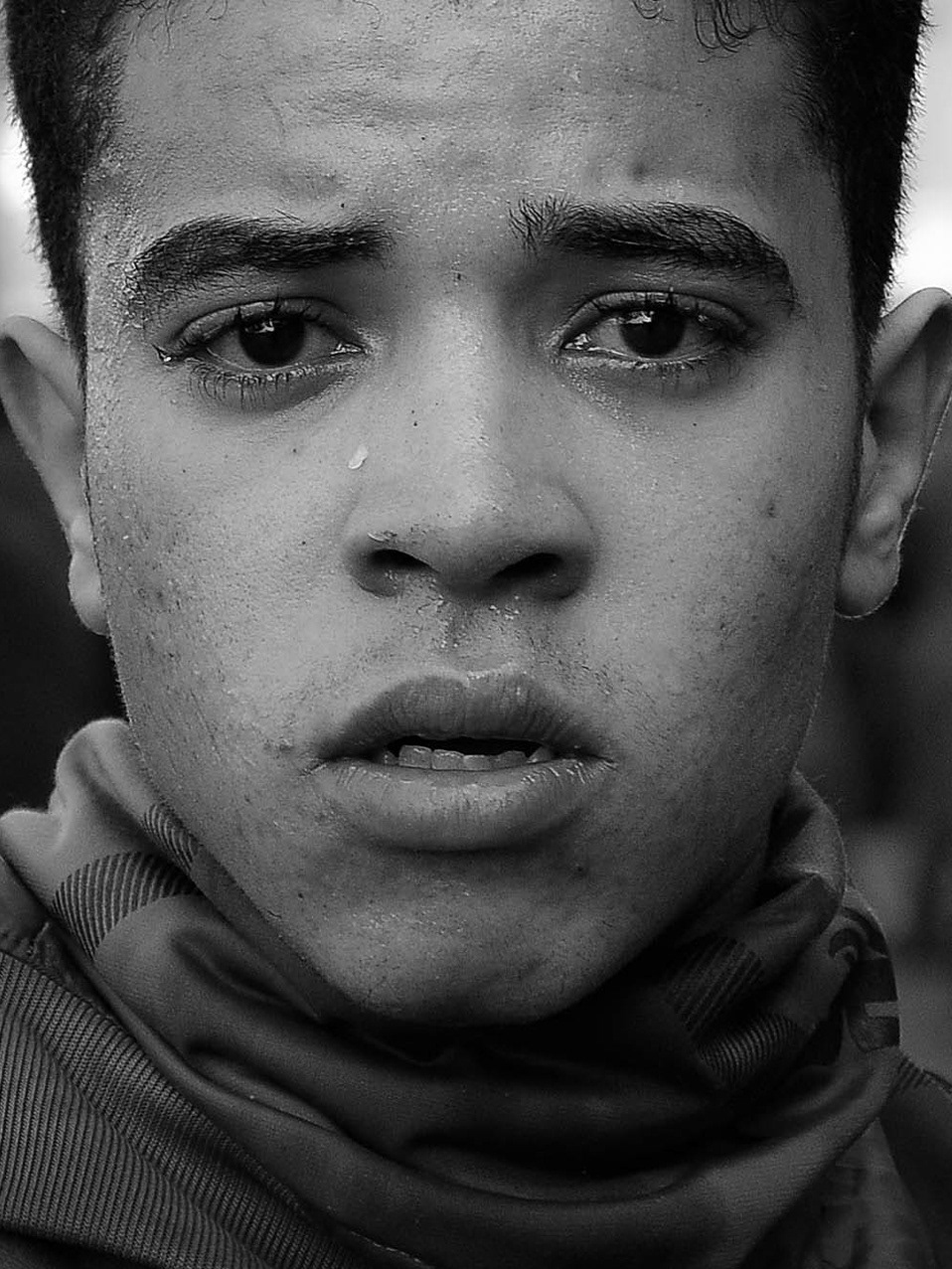

Mahmoud my friend, a young man in his thirties, points out that a large, vital area and major commercial center like "Mahatet Alraml" does not have a single planned mosque. The nearest mosques are the "Kaed Ibrahim" Mosque in "Al Azarita" , the eastern port Mosque in "Almanshia", and the fire station Mosque near "mahatet Masr". This type of absence requires filling in a random way, so we see at tram station a large mat in the middle of the square that has exceeded the role that such a mat usually plays to the point that it has become a mosque without walls or a roof. The worshipers have equipped it with a microphone and speakers, and prayers are held there regularly. There are also many of these random prayer mats in this important area.

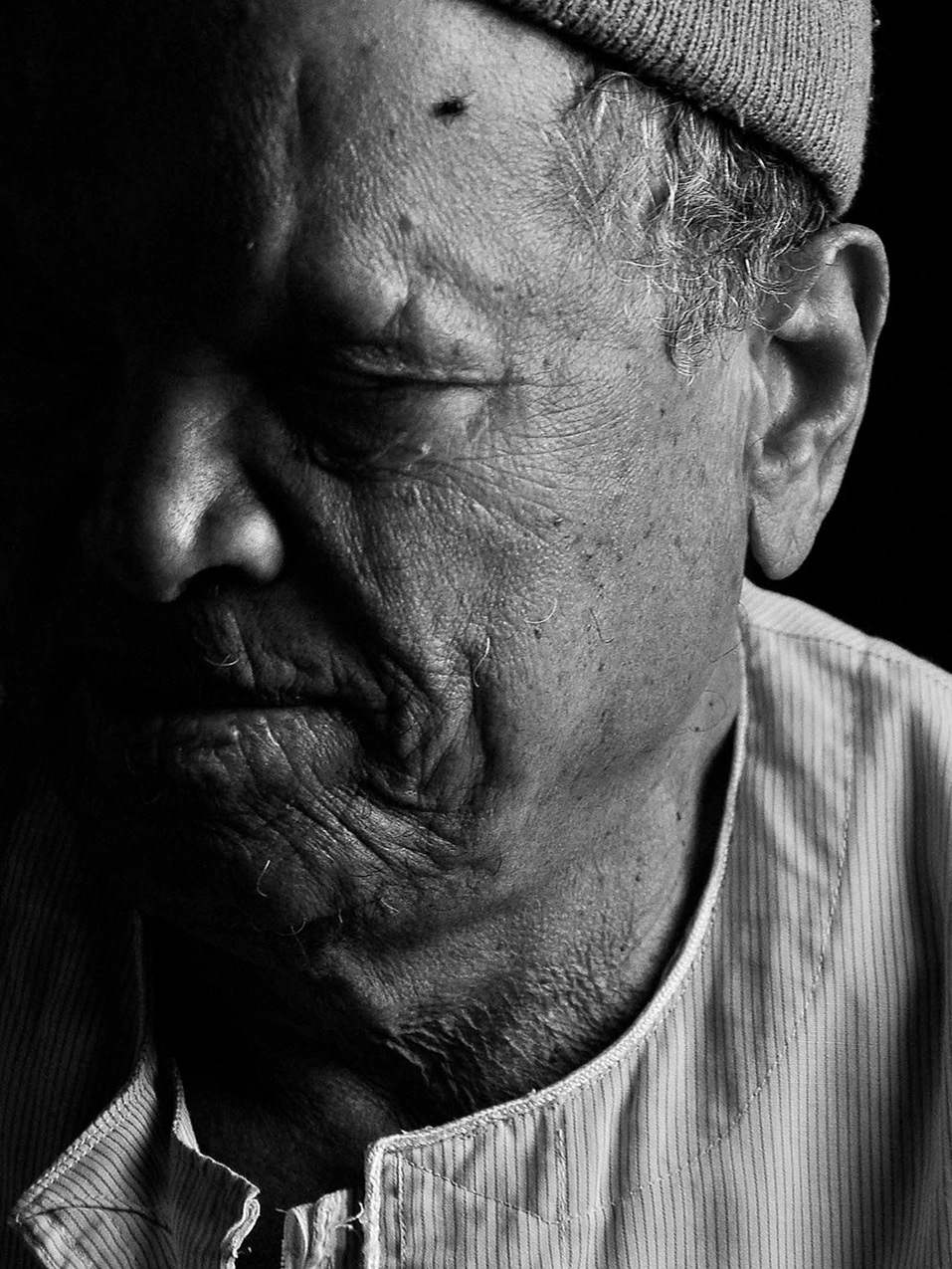

One explanation for the existence of this phenomenon is "doing good and gaining reward." Hamada, a tea vendor in one of the areas, says that his uncle and some residents of the area built the prayer mat in the hope of reward. This reason is a great incentive to do some charitable work and build prayer mats and corners or "spread" a prayer mat. There is a general knowledge in Alexandria that when contractors build a random building, they make the ground floor of the building a corner to escape taxes or demolition, and also in the hope of reward.

What personally strikes me about this activity is the exploitation of public space. I do not claim that this is an act of resistance to authority, but it is a manifestation that feels like a vent for exploiting the right to the land and the homeland to practice an activity "whatever it is" in public spaces that we are able to interact with ourselves and with our surroundings in a way that we accept as citizens.

The phenomenon of random prayer mats in Alexandria reflects the complex relationship between the right to public space, the state's planning policies, and the needs and desires of the people. It is a reminder of the importance of public space in Egyptian cities and the need for a more inclusive and sustainable approach to its management.